Divine Discontent: Disruption’s Antidote

It is nothing but a number, no different than 999,999,999,999 for all practical purposes, but we humans are not practical creatures: we attach importance to all kinds of silly

things, round numbers chief amongst them. To that end, an increasingly popular parlor question in the stocks as entertainment business is which company will be worth

$1 trillion first?

There are certainly cases to be made for Google and Microsoft and even Facebook, but most of the attention is focused on Amazon and Apple: the latter for being the

closest, and the former for growing the fastest, at least recently:

It is interesting to consider these two companies in conjunction: they couldn’t be more different, but for the one thing that makes them both so valuable.

Apple Versus Amazon

I mean it when I say these companies are the complete opposite: Apple sells products it makes; Amazon sells products made by anyone and everyone. Apple brags

about focus; Amazon calls itself “The Everything Store.” Apple is a product company that struggles at services; Amazon is a services company that struggles at product.

Apple has the highest margins and profits in the world; Amazon brags that other’s margin is their opportunity, and until recently, barely registered any profits at all. And,

underlying all of this, Apple is an extreme example of a functional organization, and Amazon an extreme example of a divisional one.

These points are all, of course, interrelated: Apple’s organizational structure, focus, and release-focused development cycle enable it to create highly differentiated

products, even as the exact same structure, focus, and development cycle underly the company’s struggles in iterative services.

Similarly, Amazon’s highly modular structure, varied businesses, and iterative approach to those businesses enable it to create services with itself as its first, best,

customer, and then extend those services to developers and retailers, even as the exact same factors lead to product disasters like the Fire Phone.

Both, taken together, are a reminder that there is no one right organizational structure, product focus, or development cycle: what matters is that they all fit together, with a

business model to match. That is where Apple and Amazon are arguable more alike than not: both are incredibly aligned in all aspects of their business. What makes

them truly similar, though, is the end goal of that alignment: the customer experience.

The iPhone Versus Disruption

The first time Apple released two different iPhone form factors in the same year was 2013. There the new form factor was the iPhone 5C, but while the industrial design

was new, the pricing wasn’t: the 5C slotted into the spot where the discontinued iPhone 5 would traditionally have gone — $100 less than the new flagship iPhone 5S.

Analysts and pundits were aghast: how could Apple not produce a truly low-price iPhone? Didn’t they know this guaranteed disruption?

I argued to the contrary in a piece entitled What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong. After recounting the many predictions by the father of disruption that the iPhone would not

be a success, I came up with three specific reasons why Apple seemed immune to disruptive gravity:

- First, it was folly to presume that consumers were rational, at least to the extent that rationality could be reduced to easily articulable features balanced agains price (or appreciating that round numbers aren’t anything special).

- Second, there are many attributes of a product that can’t be easily measured, but only experienced, and that they loom large when the person using the product is the same as the person buying the product.

- Third, that modular products, by virtue of their prioritization of standardization and interconnectivity, would inevitably fall short on attributes directly connected to the experience of using the device.

The key paragraph is here:

The attribute most valued by consumers, assuming a product is at least in the general vicinity of a need, is ease-of-use. It’s not the only one — again, doing

a job-that-needs-done is most important — but all things being equal, consumers prefer a superior user experience. What is interesting about this attribute

is that it is impossible to overshoot.

The term “overshoot” is right out of disruption theory. Christensen writes in his seminal book, The Innovator’s Dilemma:

The second element of the failure framework, the observation that technologies can progress faster than market demand…means that in their efforts to

provide better products than their competitors and earn higher prices and margins, suppliers often “overshoot” their market: They give customers more than

they need or ultimately are willing to pay for. And more importantly, it means that disruptive technologies that may underperform today, relative to what users

in the market demand, may be fully performance-competitive in that same market tomorrow.

This was the basis for insisting that the iPhone must have a low-price model: surely Apple would soon run out of new technology to justify the prices it charged for high-

end iPhones, and consumers would start buying much cheaper Android phones instead!

In fact, as I discussed in after January’s earnings results, the company has gone in the other direction: more devices per customer, higher prices per device, and an

increased focus on ongoing revenue from those same customers. Yesterday’s results were mostly more of the same: wearables were up a lot (more devices per

customer); ASP’s were down from last quarter but still 11% higher than a year ago;

services revenue, meanwhile, shot through the roof for reasons that are still a bit unclear, but impressive nonetheless.

Also the same was a very modest increase in the number of iPhone sold: 3% more than a year ago. Apple seems to have mostly saturated the high end, slowly adding

switchers even as existing iPhone users hold on to their phones longer; what is not happening, though, is what disruption predicts: Apple isn’t losing customers to low-

cost competitors for having “overshot” and overpriced its phones. It seems my thesis was right: a superior experience can never be too good — or perhaps I didn’t go far

enough.

Amazon and Divine Discontent

Jeff Bezos has been writing an annual letter to shareholders since 1997, and he attaches that original letter to one he pens every year. It included this section entitled

Obsess Over Customers:

From the beginning, our focus has been on offering our customers compelling value. We realized that the Web was, and still is, the World Wide Wait.

Therefore, we set out to offer customers something they simply could not get any other way, and began serving them with books. We brought them much

more selection than was possible in a physical store (our store would now occupy 6 football fields), and presented it in a useful, easy-to-search, and easy-

to-browse format in a store open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. We maintained a dogged focus on improving the shopping experience, and in 1997

substantially enhanced our store. We now offer customers gift certificates, 1-Click shopping, and vastly more reviews, content, browsing options, and

recommendation features. We dramatically lowered prices, further increasing customer value. Word of mouth remains the most powerful customer

acquisition tool we have, and we are grateful for the trust our customers have placed in us. Repeat purchases and word of mouth have combined to make

Amazon.com the market leader in online bookselling.

Over the last 20 years Amazon has dramatically changed, but Bezos’ annual focus on consumers has not. This year, after highlighting just how much customers love

Amazon (answer: a lot), Bezos wrote:

One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static — they go up. It’s human nature. We didn’t ascend

from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way, and yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s

‘ordinary’. I see that cycle of improvement happening at a faster rate than ever before. It may be because customers have such easy access to more

information than ever before — in only a few seconds and with a couple taps on their phones, customers can read reviews, compare prices from multiple

retailers, see whether something’s in stock, find out how fast it will ship or be available for pick-up, and more. These examples are from retail, but I sense

that the same customer empowerment phenomenon is happening broadly across everything we do at Amazon and most other industries as well. You

cannot rest on your laurels in this world. Customers won’t have it.

Critically, when it comes to Internet-based services, this customer focus does not come at the expense of a focus on infrastructure or distribution or suppliers: while those

were the means to customers in the analog world, in the online world controlling the customer relationship gives a company power over its suppliers, the capital to build

out infrastructure, and control over distribution. Bezos is not so much choosing to prioritize customers insomuch as he has unlocked the key to controlling value chains in

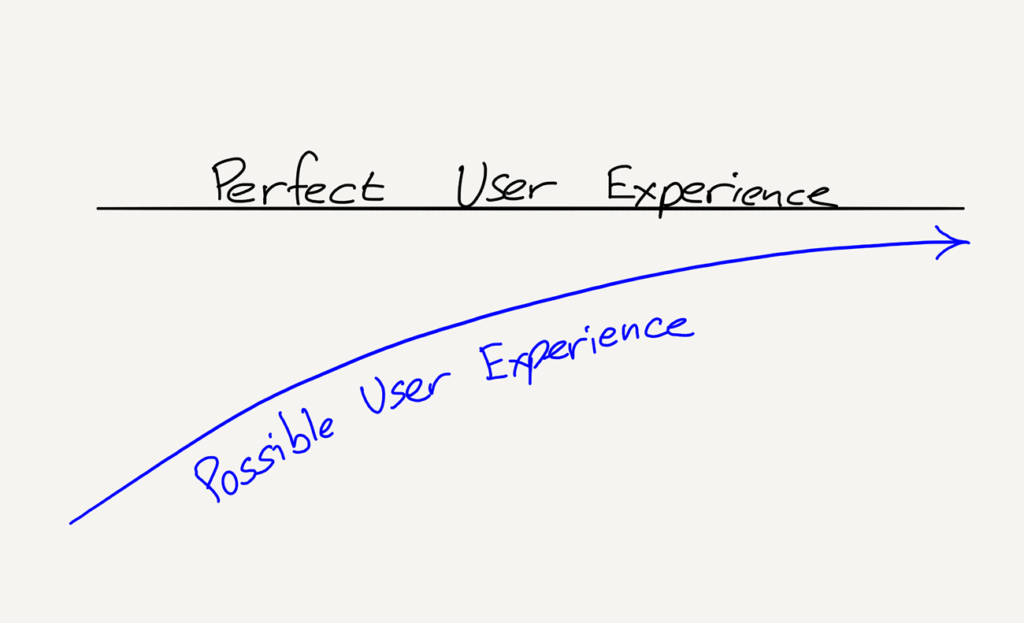

Bezos’s letter, though, reveals another advantage of focusing on customers: it makes it impossible to overshoot. When I wrote that piece five years ago, I was thinking of

the opportunity provided by a focus on the user experience as if it were an asymptote: one could get ever closer to the ultimate user experience, but never achieve it:

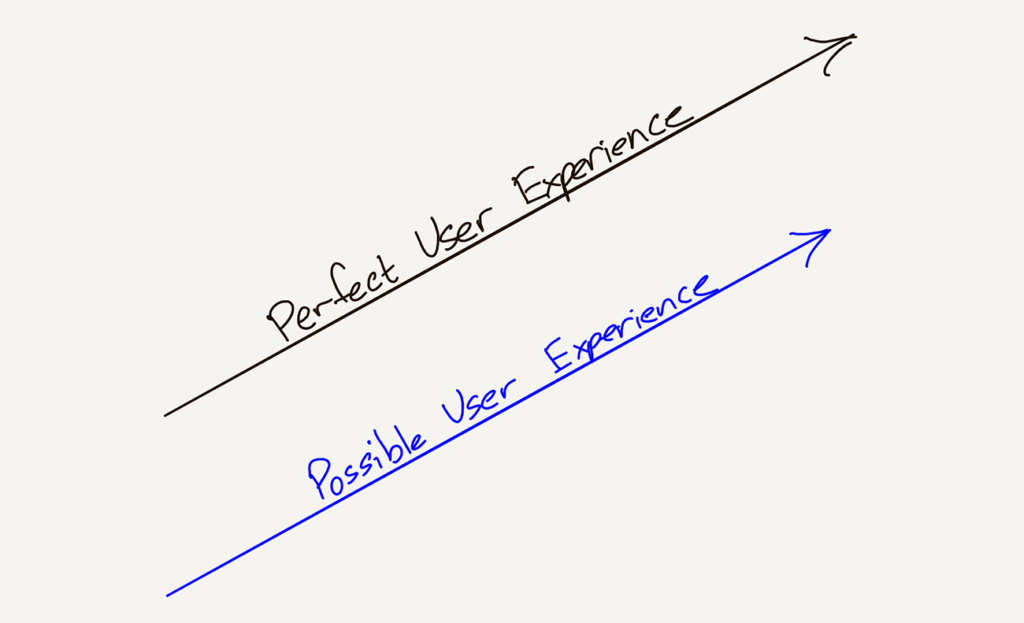

In fact, though, consumer expectations are not static: they are, as Bezos’ memorably states, “divinely discontent”. What is amazing today is table stakes tomorrow, and,

perhaps surprisingly, that makes for a tremendous business opportunity: if your company is predicated on delivering the best possible experience for consumers, then

your company will never achieve its goal.

In the case of Amazon, that this unattainable and ever-changing objective is embedded in the company’s culture is, in conjunction with the company’s demonstrated ability

to spin up new businesses on the profits of established ones, a sort of perpetual motion machine; I’m not sure that Amazon will beat Apple to $1 trillion, but they surely

have the best shot at two.

The Disruption Antidote

This analysis applies to Facebook and Google, two of the other companies in that chart, more than you might expect. While the two companies’ revenues are based on

advertising, the attractiveness to advertisers rests on consumers using both services.

Both, though, are disadvantaged to an extent because their means of making money operate orthogonally to a great user experience; both are protected by the fact would-

be competitors inevitably have the same business model.

That is why, for all four companies, the first place to look for weaknesses is not in the supplier base or distribution or even regulation: it is with the end users. That is why it

matters that Amazon is the most popular company in the United States, why Apple and Google continue to have two of the most respected brands, and why Facebook is

right to be more concerned about the PR effect of its scandals than the regulatory ones. Owning the customer relationship by means of delivering a superior experience is

how these companies became dominant, and, when they fall, it will be because consumers deserted them, either because the companies lost control of the user

experience (a danger for Facebook and Google), or because a paradigm shift made new experiences matter more (a danger for Google and Apple).

Source:Stratechery

- 上海工商

- 上海网警

上海工商 - 网络社会

征 信 网 - 沪ICP备

06014198号-9 - 涉外调查

许可证04870